Inside the Mind of an Attacker: How Contextual Security Can Save Your Cloud

Cloud Security Analyst at Cyscale

Tuesday, September 19, 2023

When public cloud providers such as Google Cloud and AWS first appeared, their benefits were hard to ignore. And although companies were reluctant to put their infrastructure and applications in the hands of a different company, cloud solutions have grown in popularity.

With more and more complex setups, it is hard for an organization to understand and keep track of the implication of every resource they have in the cloud, the risk it poses to the entire infrastructure or how many other assets it impacts.

I believe the future of cloud security is contextual security. To fully understand how secure an asset is, you need to understand what users have permissions to interact with it and what resources it communicates with. It might seem that a VM is completely secure because you put it behind a firewall, but if a compromised user can access it, it’s game over.

The perfect recipe for contextual security is a Cloud Security Knowledge Graph. Based on it, we can represent in a visual and interactive way how cloud resources interact, what kind of relations they have, what users have permissions to read/write on them, and so on.

To illustrate my point, I will show you some scenarios where the difference between a secure cloud and a breach is made by fixing misconfigurations and limiting users' access. These measures are easier to identify using a graph, because it helps you understand the risks your environment is exposed to.

Case Study

Let’s assume we use BigQuery in Google Cloud for a health analytics application. We have a table that contains some datasets of patients from a hospital, including PII data. These datasets are very valuable and cannot fall in the hands of outsiders.

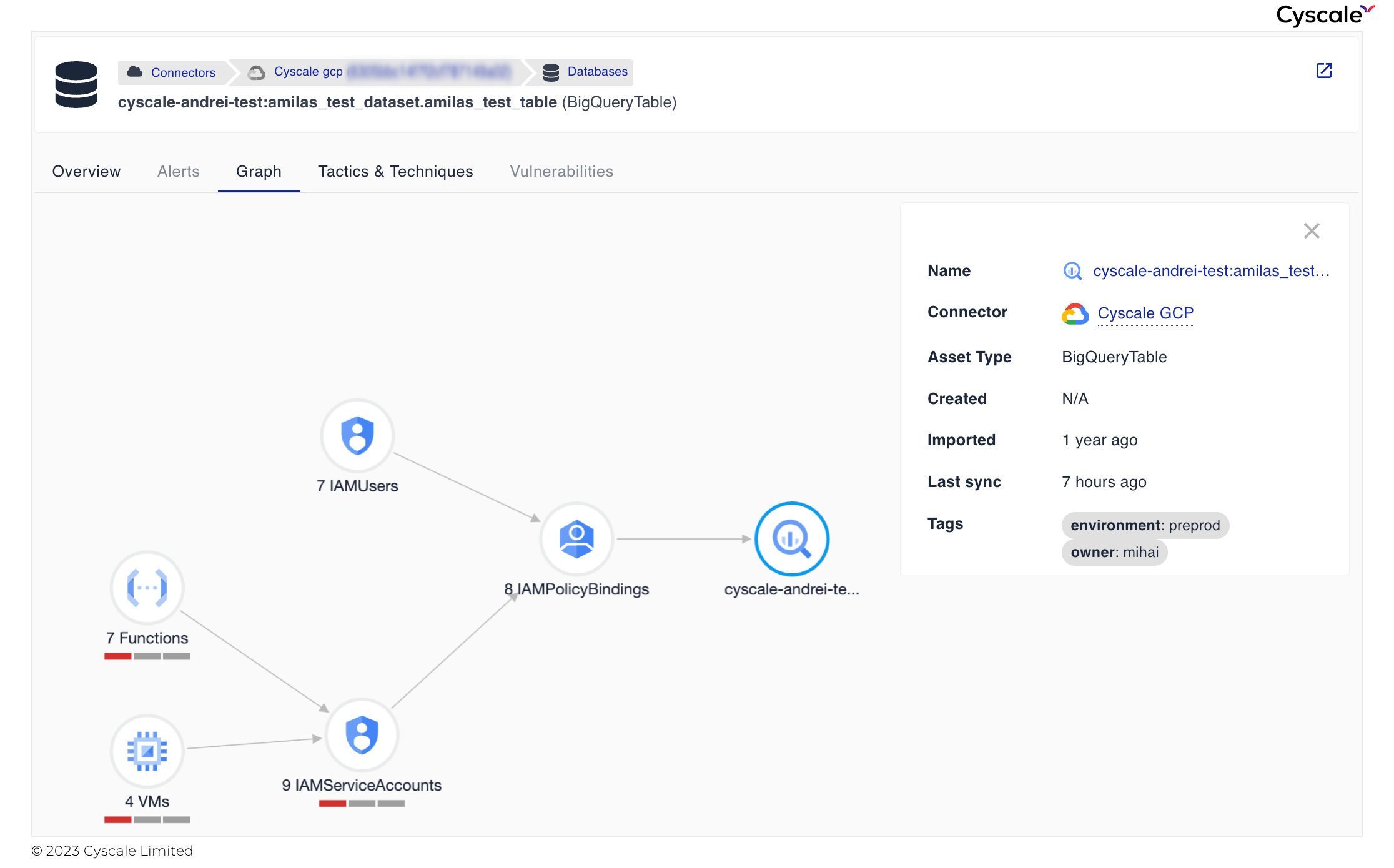

Now, we want to make sure that the data is securely stored. We look at the BigQuery table’s graph to see if the table poses any risk and, low and behold, it does!

We can observe, in the image above, that no less than 7 Cloud Functions and 4 VMs can access it across 9 Service Accounts that have permissions on the BigQueryTable, as well as 7 IAM Users. Does this alarm you? It should.

But just because a VM, or a function, can have access to the table does not mean anything, right? Wrong! I’m going to show you exactly how bad things can get in this situation. I’m going to put my hacker shoes on and show you potential scenarios that might lead to data being stolen.

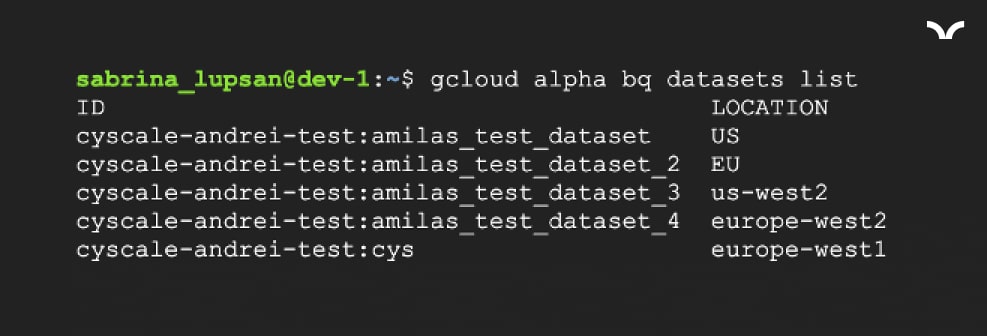

Scenario 1: compromised VM

Out of the 4 VMs that we see in the image, one is an Internet-facing one. The compute instance “dev-1” hosts an application that has the Log4J vulnerability, a classic. A hacker leverages the vulnerability and gains access to the instance. If they take over an IAMUser with the Compute Instance Admin role, or obtain SSH access to the VM, the disaster begins. Because a Service Account is associated to the VM, the attacker has that account’s permissions. In our scenario, the application running on the Instance needs to process data in the dataset, so the associated Service Account was given the roles/bigquery.dataEditor permission.

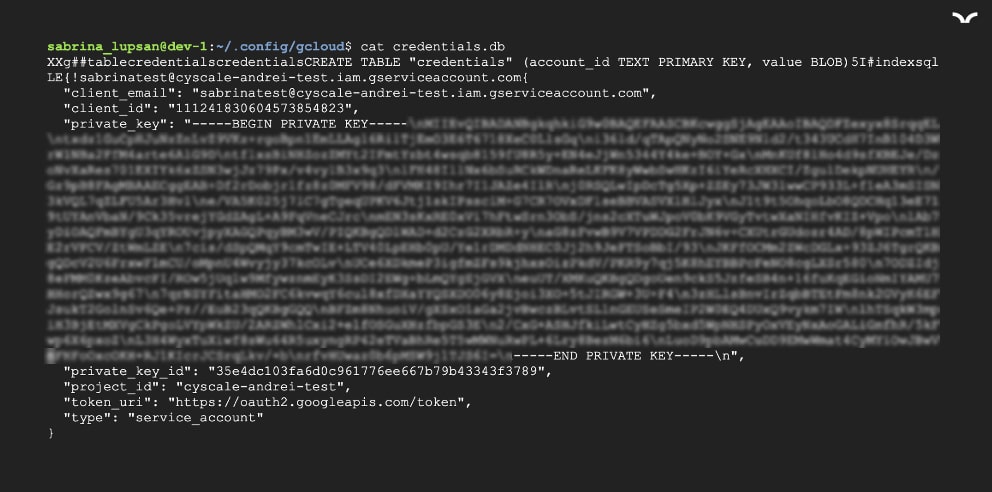

Moreover, in a VM, credentials used to manually authenticate are stored on the Compute Instance after the first time a user authenticates as a Service Account, in /.config/gcloud/credentials.db, as you can see in the image below.

This is a standard location and it stores the last private key that was used to authenticate as a Service Account. You can also find access tokens in the same folder, in access_tokens.db. Moreover, you can see any other private keys used previously (which may still be valid, if they were not deleted in the Google Cloud Console) in /.config/gcloud/legacy_credentials/

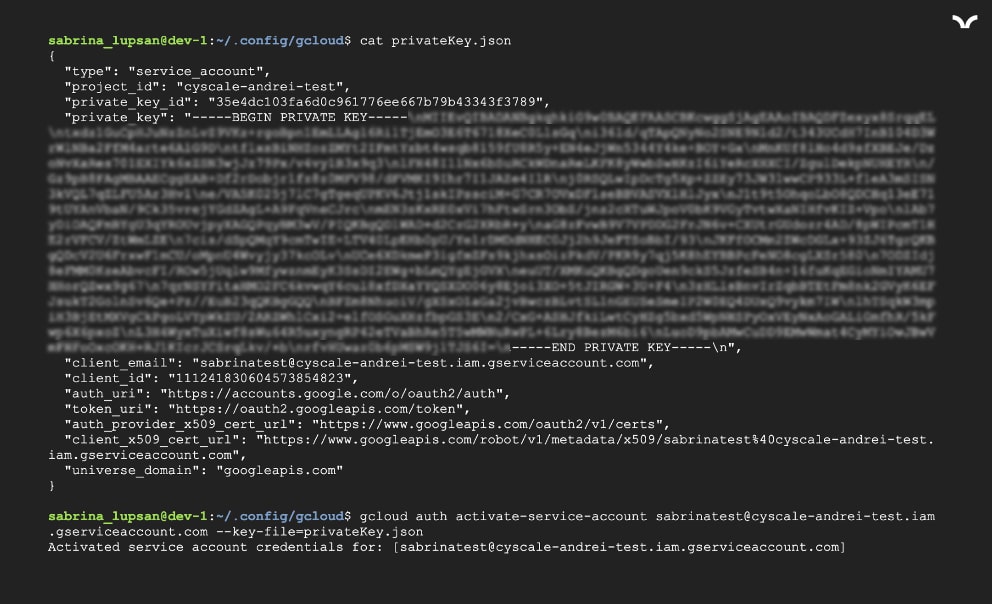

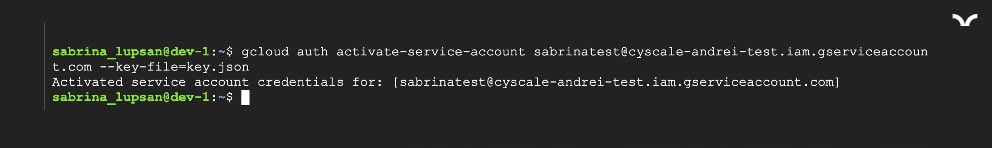

Looking at the file credentials.db, we notice that the information is not stored in the standard format for a private key for a Service Account. With a few adjustments, we obtain a valid private key that we then use to authenticate. To authenticate as a Service Account with a private key, simply use the following command:

gcloud auth activate-service-account <serviceAccountEmail> --key-file=<keyFile>

However, what happens when no one has authenticated as a Service Account on the VM? There is no credentials.db file (actually, there is no .config folder).

Developers tend to find ways to do things faster, and they get comfortable. It is not uncommon to find secrets in environment variables or plain-text files. If a developer were to store a secret key file on the Compute Instance, we could abuse it. Simply log in using the private RSA key file:

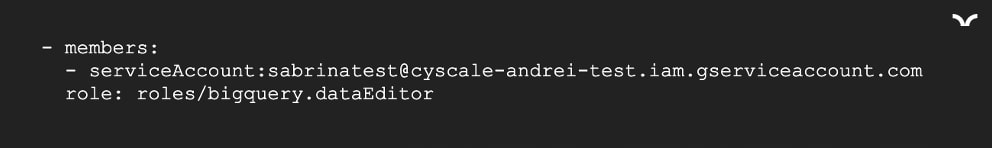

Checking the current permissions, and… bingo! roles/bigquery.dataEditor is one of the available roles.

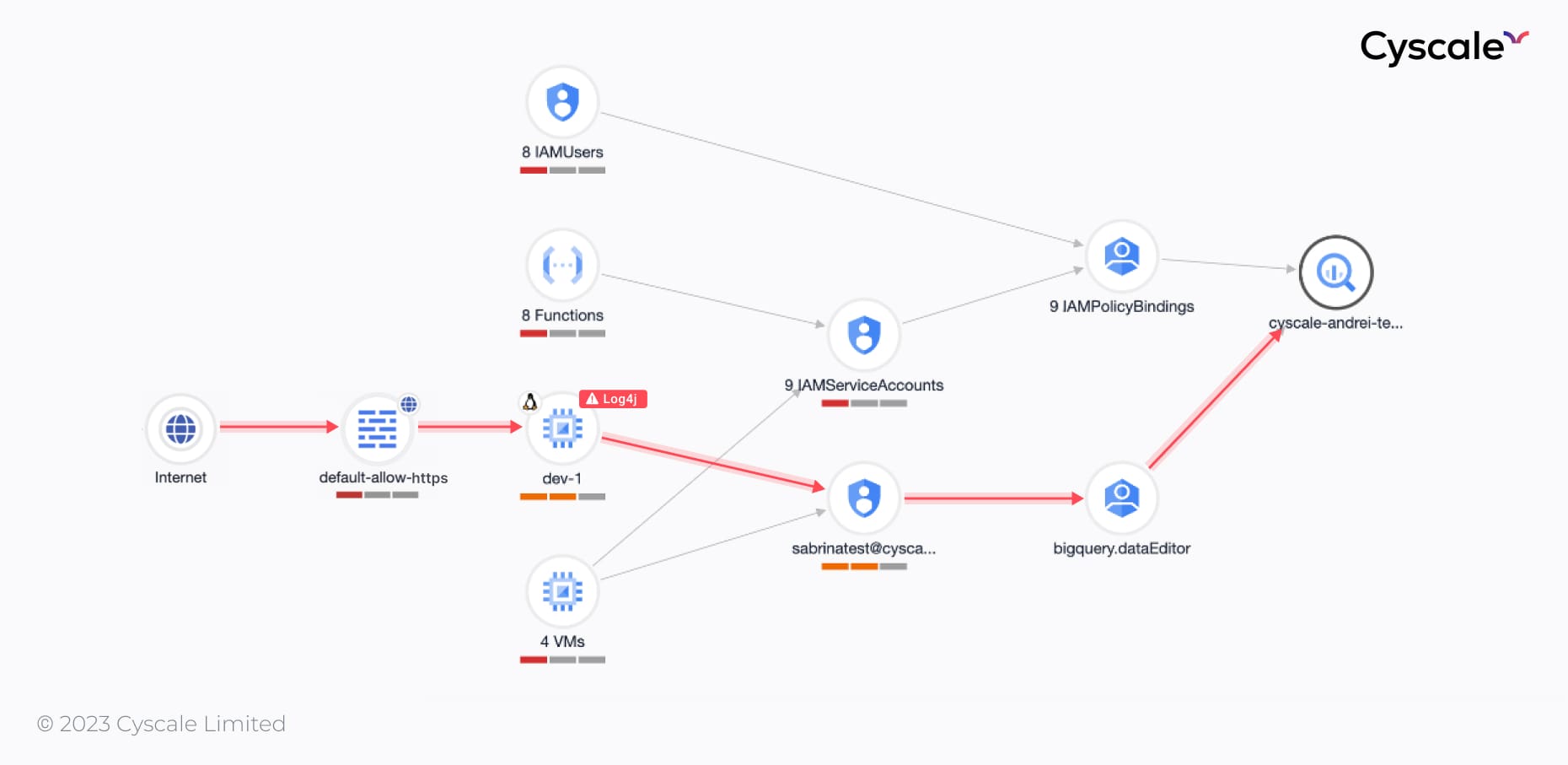

If we expand the graph’s nodes that we used in this chain of attacks, you can clearly see the attack path:

With the bigquery.dataEditor role, the attacker can now:

- view data and metadata,

- modify data and metadata,

- delete tables.

This breach could be avoided by:

- ensuring the VM does not have vulnerabilities, and patching the Log4J one,

- isolating the Compute Instance from the Internet by closing the exposed port, if possible,

- restricting the Service Account’s permissions as much as possible,

- making sure secrets are cleared from the VM files.

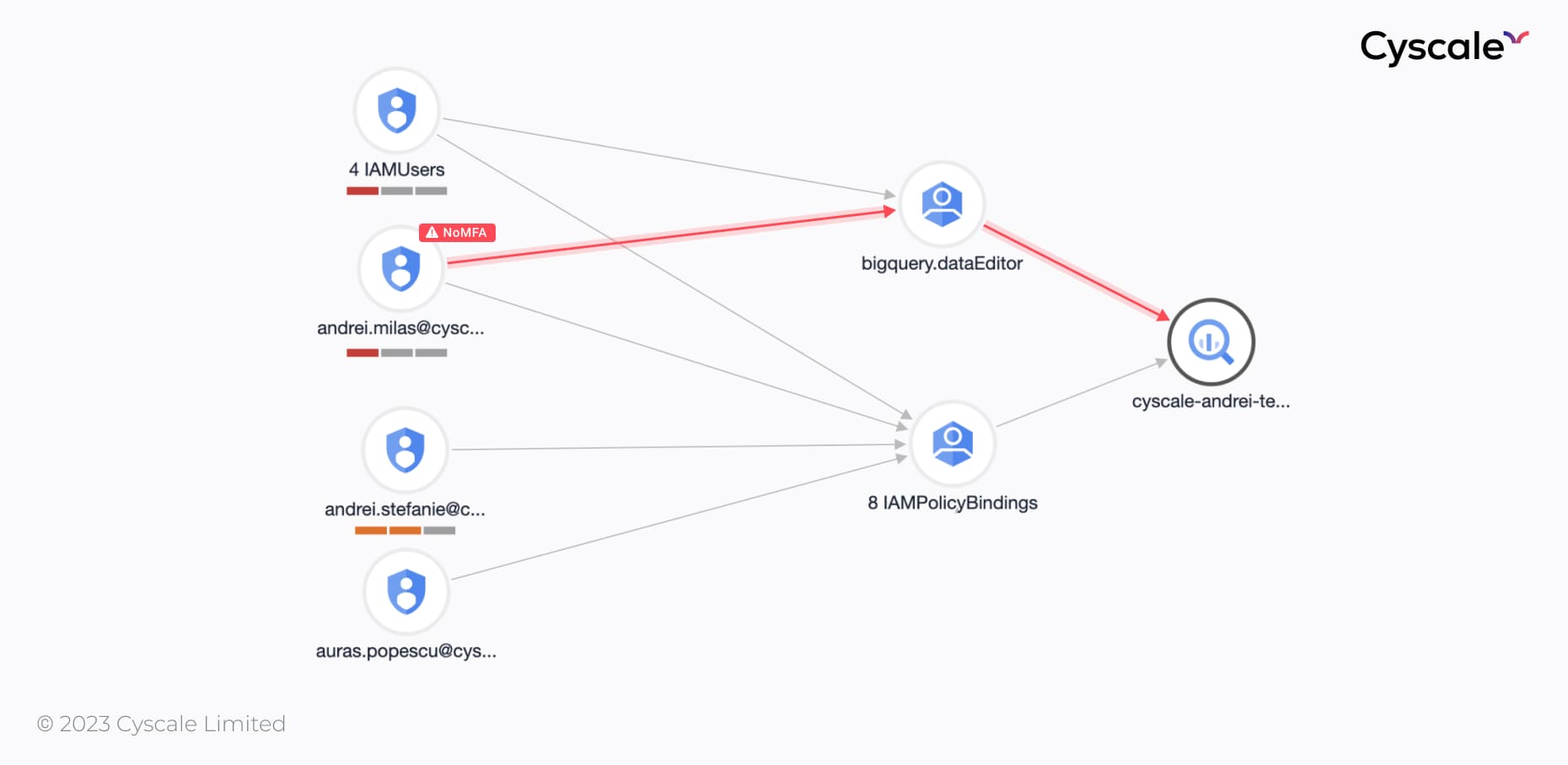

Scenario 2: compromised user

Expanding the Users node, we see that there are three users that have access to the BigQueryTable.

If a hacker were to take over any of those accounts, for example, by stealing credentials, our customer’s data would be at risk. If one of the three users that have access to the table does not have MFA enforced, then the attacker can compromise the account.

Enabling MFA would prevent this.

Besides this, a common mistake is focusing on protecting your environment from the outside, and forgetting about your own users. If one of the employees in the organization has too many permissions, they may produce damage without intention. By exploring the account and looking at resources, a user can accidentally modify or delete an asset.

This is why the Least Privilege Principle is so important – always limit the users’ access as much as possible and only assign the necessary permissions.

We believe that context is the future of cloud security. We’ve seen how the most simple relations between assets can be leveraged by attackers to take over cloud assets; and if your customers’ data is stored in those assets, the greater the prize is for hackers – and they will do anything to get it.

Cloud Security Analyst at Cyscale

Sabrina Lupsan merges her academic knowledge in Information Security with practical research to analyze and strengthen cloud security. At Cyscale, she leverages her Azure Security Engineer certification and her Master's in Information Security to keep the company's services at the leading edge of cybersecurity developments.

Further reading

Cloud Storage

Misconfigurations

Build and maintain a strong

Security Program from the start.

Cloud Compliance in

2023: An In-Depth Guide

The whitepaper talks about ISO 27001, SOC 2, PCI-DSS, GDPR, HIPAA.

Download WhitepaperShare this article

Stay Connected

Receive our latest blog posts and product updates.

TOP ARTICLES

CSPM

Our Compliance toolbox

Check out our compliance platform for cloud-native and cloud-first organizations:

LATEST ARTICLES

What we’re up to

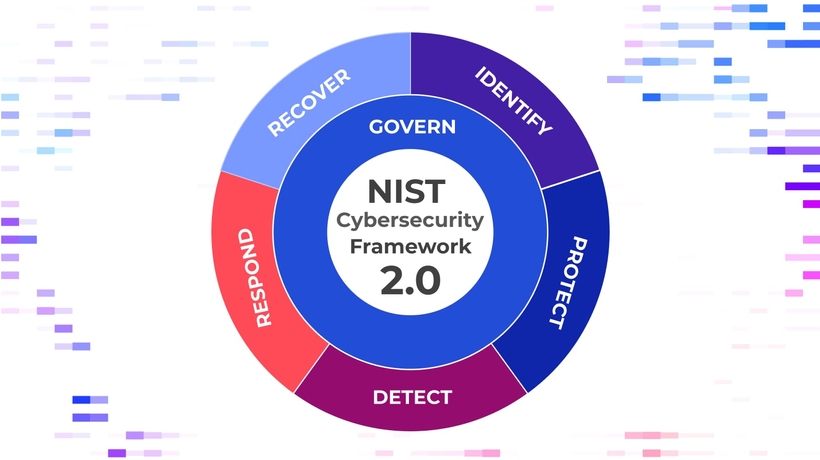

NIST CSF 2.0: A Detailed Roadmap for Modern Cybersecurity